Radical Preaching

Can preaching again have something to say?

This blog marks the attempt to bring the theological vision of Radical Orthodoxy into the worship and preaching of the local church.

Monday, October 31, 2005

Saturday, October 29, 2005

Staring in the Mirror

When I attended West Point, there were many arrogant people, but there was one who took the cake. His name was Pete, and Pete was convinced just how smart and beautiful he was. Every story featured him as the great hero who slayed dragons, saved wenches, and restored good and justice to the world. He was a classic “topper.” You tell a story, and he tops it. He loved to look at himself in the mirror. Anytime he passed a mirror, he just could not help himself. He had to stop and take a look. He had to gaze at his hair and remind himself just how handsome he was.

Have you ever heard the story of Narcissus? Narcissus was a similar man, celebrated in Greek mythology for his great beauty. He was so handsome that the nymphs all fell in love with him, but he rejected all of their efforts. As a curse, Narcissus was made to fall in love with his own image. Narcissus fell so deeply in love with himself, that he sat by the riverbank and gazed at his own reflection longingly. Many came and begged him to leave, begged him to eat and to drink, to remember all the good things of life, but Narcissus sat there and stared at his reflection until he died. Psychologists tell us that narcissism is a condition where we fall in love with our own beauty until we are paralyzed gazing in the mirror at ourselves.

In our Gospel reading today, Jesus accuses the Pharisees of a narcissism of sorts. If you remember last week, I told you how the Pharisees sought, above all else, to protect their identity as Jews, to remain faithful in a world gone mad. They desperately sought to form a people who would live by the Law in every aspect of their life. To some degree, they were successful. Their piety and hard work allowed them a certain degree of financial security. Their devotion to the faith won them prestige in local communities. If not powerful, they were at least respected. As time passed, they began to lose sight of their purpose. They began to fall in love with their own works. Their goal began to be the maintenance of the structures they built and keeping up the traditions they began. They lost sight of their true end: the worship of God. Instead, they fell in love with the creation of their own hands. They began to look in the mirror and admire their own reflection.

Jesus, of course, comes to town and smashes their mirror to little pieces. After they fail in their attempts to trap him, they withdraw to conspire how best to kill him. As they leave, Jesus begins to speak to his disciples and to the gathered crowd. He says, “The scribes and Pharisees sit on the seat of Moses, so practice and observe whatever they tell you—but not what they do. For they preach, but do not practice” (Mt. 23:2-3, ESV). He goes on to describe that the Pharisees love to lay burdens on people’s shoulders, but move not even one finger to help lift the burden. They love to dress the part, making their phylacteries broad and their fringes long. However, they do not attend to the meatier aspects of the Law: justice and mercy and faithfulness. Not only do they love to be seen, they also love to be exalted- in the synagogues and at the feasts. They love to be exalted by others, to be called “Master” and “Teacher.” In this sermon, Jesus excoriates them for losing sight of the end of the Law, for falling in love with their own works. He condemns them for their narcissism and calls for his followers and the crowd to turn away from the mirror and to look at the world differently.

The question I have today is whether we are significantly different from the Pharisees. Clearly, we Nazarenes believe ourselves to be different. We have cut loose from dead rituals and symbols such as phylacteries and fringes. We deny the place of any sort of salvation from mere appearance. But I wonder if we are not gazing at the other side of the same mirror. I wonder if we peeked around the corner, if we might find that the Pharisee who stares back reflects us. As I prepared for this sermon, I was shocked to find that most of the commentaries and sermons that I read reproduced the very thing that Jesus condemns in this passage. Jesus tells his disciples and the crowd to obey the teachings of the Pharisees and Scribes because they sit on the seat of Moses. They are the rightful proclaimers of the Law. He tells them only not to do as the Pharisees do because they do not practice what they preach. He then lays this out with specific charges: They bind up people with heavy burdens but do not help to lift that burden; they love to dress the part of a holiness people but do not perform justice, mercy, and faithfulness in their daily lives; they love to be exalted in the synagogues and at feasts but have lost all sight of humbly coming before God. Most sermons and commentaries read Jesus as placing binding up sin in opposition to loosing the burdens of sin, as placing the appearance of holiness in opposition to the performance of holiness, as placing exaltation in opposition to humility. This reading causes them to read Jesus’ judgment on the Pharisees and scribes back the other way. Jesus does not place these in tension and opposition with each other. He does not call for an either/or but a both/and. He calls for his disciples to both bind and loose, to appear and perform holiness, to be both humble and exalted. To miss this point is to run the great risk of standing on one side of the mirror or the other, and finding some type of Pharisee on either side.

In order to avoid this powerful temptation, we must really hear what it is that Jesus calls for us to be and do.

First, we must remember the work that has been given us to do. We are created in Christ’s image, and we are given good work to do. We are called to participate in God’s work of saving and restoring fallen creation. In Matthew’s Gospel, this is known as the ministry of the keys. In Matthew 16, Jesus gives the keys to the kingdom to Peter and tells him that he has the authority to both bind and loose. The church is to go forth and to bind up the world in its sins, to live and proclaim faithfully that to not worship the God revealed in Jesus Christ is to sin and will lead to all forms of death and despair. However, to proclaim judgment is not enough. We are also called, as Christ’s body, to loose sinners from the burden of sin. The key works both ways, not only to bind up in chains, but also to loose us from our sins.

Second, we must remember out baptism. Jesus calls for us to have the same appearance of holiness portrayed by the Pharisees and scribes with their broad phylacteries and long fringes. He also calls for us to attend to the meat of the Gospel: justice, mercy, and faithfulness. As Jeremiah tells us, we are to have the law written on our hearts and not on stone. As Paul tells us, we are to put on Christ. In baptism, we die to self to be raised in the glorious beauty of Jesus Christ. We literally put on his image and bear it to the world. Thus, our phylacteries and fringe appear as we remember that in baptism all men and women are our brothers and sisters, that in baptism there is no slave or free, Jew or Gentile, male or female, but that we are all one in Christ Jesus.

When I began teaching, my mentor teacher told me one day when she discovered I was a preacher also that she was glad she took her children to Sunday School every week. I told her I thought that was great, to which she responded, “Yes, everyone should go to church as kids because it teaches them basic morality for their lives.” We so often forget that the church is more than a place for moral formation, an add-on to our lives. The church is the baptized community, a people who have put on Christ and now carry Christ to a sin-sickened and dying world.

Third, we must remember the Eucharist. Jesus condemns the Pharisees for their desire to be exalted, to sit in the best seats and to be called Master in public. In the Eucharist, we remember that Christ was exalted in his humility. He, who is the King of all Glory, gave up his throne to come to earth. In the Eucharistic feast, we remember that Christ was humble in his life and practices and in the way that he faced death on the Cross. However, he was exalted in his humility. In the Eucharistic feast, we remember that we are not humble for humility’s sake. We are not called to be masochists. Instead, we are called to be His Body, the Church. To remember our identity in Him and to give thanks, rejoicing in what is to come when the last will be first and the first will be last.

We live in a day and age when the individual is celebrated, elevated, and exalted. We live in age of cultural narcissism. It is very easy to fall into this sin, to gaze at ourselves in the mirror. We live in dangerous times, and it is much easier to build fences and put up walls than it is to go out into the world and risk everything. It is much easier to ignore what is going on “out there” and remain in the comfort of the world we create for ourselves. However, baptism reminds us that our life is not our own; we have now put on Christ. The Eucharist reminds us that God is remaking the world, and invites us as his body to participate in that glorious work. The ministry of the keys reminds us that there is good and risky work to do in the world. We must go out and name sin, bind up sinners by speaking the truth in love, and then set them free in the name of Jesus Christ.

The powerful temptation we face today is to be narcissistic, to believe that we are pretty and perfect, just as we are. When we do this, we seek only to glorify ourselves. We begin to believe that we are the center of the world. We will build all kinds of things: programs, buildings, and ministries. But these will all be to celebrate our own power and glory.

During the Civil War, George McClellan took a faltering Union Army and built it into the most powerful army in the world. He painstakingly trained and disciplined his army until it worked like a machine. In his mind it was both perfect and beautiful. In his worship of his creation, he forgot that armies are created for one purpose: to fight wars. Finally, Abraham Lincoln, exasperated by McClellan’s delays wrote the general and asked him, “General McClellan, if you are not doing anything, may I borrow your army, I have a war to fight.”

All around us today, the world is mired in the depths and despair of sin and evil. All around us people are perishing outside the saving love of our Lord. Will we be a people that remember that the Church has one end: to be the Body of Christ, His flesh and blood presence in a world gone mad. Can we begin to move out and tear down the walls and gates that we have erected in a vain attempt to protect ourselves? Will we journey out, in His name, to do the glorious work he has given us?

Have you ever heard the story of Narcissus? Narcissus was a similar man, celebrated in Greek mythology for his great beauty. He was so handsome that the nymphs all fell in love with him, but he rejected all of their efforts. As a curse, Narcissus was made to fall in love with his own image. Narcissus fell so deeply in love with himself, that he sat by the riverbank and gazed at his own reflection longingly. Many came and begged him to leave, begged him to eat and to drink, to remember all the good things of life, but Narcissus sat there and stared at his reflection until he died. Psychologists tell us that narcissism is a condition where we fall in love with our own beauty until we are paralyzed gazing in the mirror at ourselves.

In our Gospel reading today, Jesus accuses the Pharisees of a narcissism of sorts. If you remember last week, I told you how the Pharisees sought, above all else, to protect their identity as Jews, to remain faithful in a world gone mad. They desperately sought to form a people who would live by the Law in every aspect of their life. To some degree, they were successful. Their piety and hard work allowed them a certain degree of financial security. Their devotion to the faith won them prestige in local communities. If not powerful, they were at least respected. As time passed, they began to lose sight of their purpose. They began to fall in love with their own works. Their goal began to be the maintenance of the structures they built and keeping up the traditions they began. They lost sight of their true end: the worship of God. Instead, they fell in love with the creation of their own hands. They began to look in the mirror and admire their own reflection.

Jesus, of course, comes to town and smashes their mirror to little pieces. After they fail in their attempts to trap him, they withdraw to conspire how best to kill him. As they leave, Jesus begins to speak to his disciples and to the gathered crowd. He says, “The scribes and Pharisees sit on the seat of Moses, so practice and observe whatever they tell you—but not what they do. For they preach, but do not practice” (Mt. 23:2-3, ESV). He goes on to describe that the Pharisees love to lay burdens on people’s shoulders, but move not even one finger to help lift the burden. They love to dress the part, making their phylacteries broad and their fringes long. However, they do not attend to the meatier aspects of the Law: justice and mercy and faithfulness. Not only do they love to be seen, they also love to be exalted- in the synagogues and at the feasts. They love to be exalted by others, to be called “Master” and “Teacher.” In this sermon, Jesus excoriates them for losing sight of the end of the Law, for falling in love with their own works. He condemns them for their narcissism and calls for his followers and the crowd to turn away from the mirror and to look at the world differently.

The question I have today is whether we are significantly different from the Pharisees. Clearly, we Nazarenes believe ourselves to be different. We have cut loose from dead rituals and symbols such as phylacteries and fringes. We deny the place of any sort of salvation from mere appearance. But I wonder if we are not gazing at the other side of the same mirror. I wonder if we peeked around the corner, if we might find that the Pharisee who stares back reflects us. As I prepared for this sermon, I was shocked to find that most of the commentaries and sermons that I read reproduced the very thing that Jesus condemns in this passage. Jesus tells his disciples and the crowd to obey the teachings of the Pharisees and Scribes because they sit on the seat of Moses. They are the rightful proclaimers of the Law. He tells them only not to do as the Pharisees do because they do not practice what they preach. He then lays this out with specific charges: They bind up people with heavy burdens but do not help to lift that burden; they love to dress the part of a holiness people but do not perform justice, mercy, and faithfulness in their daily lives; they love to be exalted in the synagogues and at feasts but have lost all sight of humbly coming before God. Most sermons and commentaries read Jesus as placing binding up sin in opposition to loosing the burdens of sin, as placing the appearance of holiness in opposition to the performance of holiness, as placing exaltation in opposition to humility. This reading causes them to read Jesus’ judgment on the Pharisees and scribes back the other way. Jesus does not place these in tension and opposition with each other. He does not call for an either/or but a both/and. He calls for his disciples to both bind and loose, to appear and perform holiness, to be both humble and exalted. To miss this point is to run the great risk of standing on one side of the mirror or the other, and finding some type of Pharisee on either side.

In order to avoid this powerful temptation, we must really hear what it is that Jesus calls for us to be and do.

First, we must remember the work that has been given us to do. We are created in Christ’s image, and we are given good work to do. We are called to participate in God’s work of saving and restoring fallen creation. In Matthew’s Gospel, this is known as the ministry of the keys. In Matthew 16, Jesus gives the keys to the kingdom to Peter and tells him that he has the authority to both bind and loose. The church is to go forth and to bind up the world in its sins, to live and proclaim faithfully that to not worship the God revealed in Jesus Christ is to sin and will lead to all forms of death and despair. However, to proclaim judgment is not enough. We are also called, as Christ’s body, to loose sinners from the burden of sin. The key works both ways, not only to bind up in chains, but also to loose us from our sins.

Second, we must remember out baptism. Jesus calls for us to have the same appearance of holiness portrayed by the Pharisees and scribes with their broad phylacteries and long fringes. He also calls for us to attend to the meat of the Gospel: justice, mercy, and faithfulness. As Jeremiah tells us, we are to have the law written on our hearts and not on stone. As Paul tells us, we are to put on Christ. In baptism, we die to self to be raised in the glorious beauty of Jesus Christ. We literally put on his image and bear it to the world. Thus, our phylacteries and fringe appear as we remember that in baptism all men and women are our brothers and sisters, that in baptism there is no slave or free, Jew or Gentile, male or female, but that we are all one in Christ Jesus.

When I began teaching, my mentor teacher told me one day when she discovered I was a preacher also that she was glad she took her children to Sunday School every week. I told her I thought that was great, to which she responded, “Yes, everyone should go to church as kids because it teaches them basic morality for their lives.” We so often forget that the church is more than a place for moral formation, an add-on to our lives. The church is the baptized community, a people who have put on Christ and now carry Christ to a sin-sickened and dying world.

Third, we must remember the Eucharist. Jesus condemns the Pharisees for their desire to be exalted, to sit in the best seats and to be called Master in public. In the Eucharist, we remember that Christ was exalted in his humility. He, who is the King of all Glory, gave up his throne to come to earth. In the Eucharistic feast, we remember that Christ was humble in his life and practices and in the way that he faced death on the Cross. However, he was exalted in his humility. In the Eucharistic feast, we remember that we are not humble for humility’s sake. We are not called to be masochists. Instead, we are called to be His Body, the Church. To remember our identity in Him and to give thanks, rejoicing in what is to come when the last will be first and the first will be last.

We live in a day and age when the individual is celebrated, elevated, and exalted. We live in age of cultural narcissism. It is very easy to fall into this sin, to gaze at ourselves in the mirror. We live in dangerous times, and it is much easier to build fences and put up walls than it is to go out into the world and risk everything. It is much easier to ignore what is going on “out there” and remain in the comfort of the world we create for ourselves. However, baptism reminds us that our life is not our own; we have now put on Christ. The Eucharist reminds us that God is remaking the world, and invites us as his body to participate in that glorious work. The ministry of the keys reminds us that there is good and risky work to do in the world. We must go out and name sin, bind up sinners by speaking the truth in love, and then set them free in the name of Jesus Christ.

The powerful temptation we face today is to be narcissistic, to believe that we are pretty and perfect, just as we are. When we do this, we seek only to glorify ourselves. We begin to believe that we are the center of the world. We will build all kinds of things: programs, buildings, and ministries. But these will all be to celebrate our own power and glory.

During the Civil War, George McClellan took a faltering Union Army and built it into the most powerful army in the world. He painstakingly trained and disciplined his army until it worked like a machine. In his mind it was both perfect and beautiful. In his worship of his creation, he forgot that armies are created for one purpose: to fight wars. Finally, Abraham Lincoln, exasperated by McClellan’s delays wrote the general and asked him, “General McClellan, if you are not doing anything, may I borrow your army, I have a war to fight.”

All around us today, the world is mired in the depths and despair of sin and evil. All around us people are perishing outside the saving love of our Lord. Will we be a people that remember that the Church has one end: to be the Body of Christ, His flesh and blood presence in a world gone mad. Can we begin to move out and tear down the walls and gates that we have erected in a vain attempt to protect ourselves? Will we journey out, in His name, to do the glorious work he has given us?

Friday, October 28, 2005

Reading Radical Orthodoxy

In an earlier post, David asked for reading recommendations for Radical Orthodoxy. I thought I would provide sort of a rough reading list, and then others could contribute to fill in the gaps (As I am writing this, I see that Eric has already offered up an excellent list in the comments section). I will begin with introductory books/articles, and then offer up other books. I have read about ten of the RO series, so this is hardly complete. I know there are some excellent books that I have not gotten to. I will list them below, also.

Introduction to Radical Orthodoxy

1) James K. A. Smith, Introducing Radical Orthodoxy

I think Smith does a fantastic job providing an overview and introduction to RO. I confess that I skimmed the sections about the Dutch Reformed church.

2) John Milbank, "Postmodern Critical Augustinianism: A Short Summa..."

Modern Theology, 7:3 (April 1991), 225-237. This article is also contained in Graham Ward's, The Postmodern God. In this book, Catherine Pickstock also has a very good article about how modern liturgical reforms (asyndeton) altered the way we understand God, worship, and faith.

In this relatively short article, Milbank provides an overview of his theological project. I find this to be a very helpful introduction.

3) John Milbank, Catherine Pickstock, & Graham Ward. Radical Orthodoxy.

As Eric highlighted, Cavanaugh's chapter, "The City: Beyond Secular Parodies," is outstanding. Iwould also read the introduction, chapter 1 by Milbank, chapter 5 by Michael Hanby, Chapter 8 by Graham Ward, and Chapter 12 by Catherine Pickstock.

After the Introduction

John Milbank, Theology and Social Theory

This is Milbank's extraordinary critique of secular reason. It is unbelievable in its scope. Hauerwas declared that in this one book Milbank was able to "gore everyone's ox." This one will take some time to read, but he absolutely takes apart secular reason. The last chapter calls for a Trinitarian ontology and reveals how he is seeking to reappropriate Augustine.

Catherine Pickstock, After Writing: The Liturgical Consummation of Philosophy

This book supposedly won Dr. Pickstock an audience with Pope Benedict XVI when he was a Cardinal. In this book, she first takes on Derrida's reading of Plato, and then discusses how the Medieval liturgy is the culmination of philosophy, language, and art. This book is not an easy read, but a very fruitful one. I am still working my way through this one, but I love what she is doing.

John Milbank, The Word Made Strange

In the last chapter of Theology and Social Theory, Milbank begins his constructive theological project. In this book, he begins to expand on his Christology, pneumatology, and ecclesiology. There are some fantastic essays in this book. As I wrestle with this book more, I like it much more than on the first reading.

John Milbank and Catherine Pickstock, Truth in Aquinas

I must confess that I have only skimmed this book. My mentor and friend who is a church history professor at Trevecca believes that they read Aquinas correctly and dangerously so. This is by far probably the most controversial of the RO series since Thomists of all stripes have attacked it. I noticed this topic coming up quite frequently on your blog, and so I bumped it up the list. This is definitely an RO reading of Thomas. I would be interested in your thoughts.

Dan Bell, Liberation Theology after the End of History

This book is an excellent analysis of the Catholic liberation theology movement in Latin America. Bell sees that liberation theology lacked an ecclesiology capable of resisting capitalism. He provides an excellent analysis of capitalism, as well, focusing on how capitalism disciplines our desire making us into docile subjects. This is an outstanding work.

Conor Cunningham, Genealogy of Nihilism

Like Eric, I find this book to be profound. I am still working my way through it, but I see Cunningham addressing some of the frequent criticisms made of Milbank's work. I find his reading of nihilism to be fascinating.

Michael Hanby, Augustine and Modernity

I am shocked that this book does not get more attention. I read this book deeply as I read it in a directed reading I was taking on Augustine, and again in a class I took on Radical Orthodoxy. He takes apart the traditional modern claim that Augustine stands in direct line between Plato and Descartes in terms of the creation of the autonomous self. He also works through Augustine's Trinitarian theology and soteriology. Hanby articulates the idea of a doxological selfhood. This is a RO reading of Augustine.

Related to RO

William Cavanaugh, Torture and Eucharist

This is not in the RO series, but Cavanaugh has written an exceptional essay mentioned above. This book, though, provides an ecclesial example of how the core elements of RO look on the ground in resistance to the Pinochet regime. Words cannot express how excellent I find this book to be.

Stephen Long, The Goodness of God

Eric recommended Long's Divine Economy, which is published in the RO series. That is also an excellent book. However, this is my absolute favorite book of Long's (though I haven't read his most recent which I hear is also quite good).

Bell, Long and Cavanaugh are students of Hauerwas, to whom I am deeply indebted to for forming me as a Christian and a pastor. I confess that I am more Hauerwasian than RO, and that bias is probably represented in this list.

Critiques of RO

David Toole, Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo

I checked this book out on interlibrary loan, so I only had it for two weeks. It attempts to critique RO from the perspective of John Howard Yoder. Toole claims that ultimately Milbank is unable to outnarrate nihilism, because he lack an apocalyptic understanding of the world. I wish I had more time with this book because I think he raises some serious issues that RO has yet to address with regards to pacifism.

I hope this helps. There are several other books in the series as well as other related books that are coming out. I believe this is a good start.

Grace and Peace,

Scott

Introduction to Radical Orthodoxy

1) James K. A. Smith, Introducing Radical Orthodoxy

I think Smith does a fantastic job providing an overview and introduction to RO. I confess that I skimmed the sections about the Dutch Reformed church.

2) John Milbank, "Postmodern Critical Augustinianism: A Short Summa..."

Modern Theology, 7:3 (April 1991), 225-237. This article is also contained in Graham Ward's, The Postmodern God. In this book, Catherine Pickstock also has a very good article about how modern liturgical reforms (asyndeton) altered the way we understand God, worship, and faith.

In this relatively short article, Milbank provides an overview of his theological project. I find this to be a very helpful introduction.

3) John Milbank, Catherine Pickstock, & Graham Ward. Radical Orthodoxy.

As Eric highlighted, Cavanaugh's chapter, "The City: Beyond Secular Parodies," is outstanding. Iwould also read the introduction, chapter 1 by Milbank, chapter 5 by Michael Hanby, Chapter 8 by Graham Ward, and Chapter 12 by Catherine Pickstock.

After the Introduction

John Milbank, Theology and Social Theory

This is Milbank's extraordinary critique of secular reason. It is unbelievable in its scope. Hauerwas declared that in this one book Milbank was able to "gore everyone's ox." This one will take some time to read, but he absolutely takes apart secular reason. The last chapter calls for a Trinitarian ontology and reveals how he is seeking to reappropriate Augustine.

Catherine Pickstock, After Writing: The Liturgical Consummation of Philosophy

This book supposedly won Dr. Pickstock an audience with Pope Benedict XVI when he was a Cardinal. In this book, she first takes on Derrida's reading of Plato, and then discusses how the Medieval liturgy is the culmination of philosophy, language, and art. This book is not an easy read, but a very fruitful one. I am still working my way through this one, but I love what she is doing.

John Milbank, The Word Made Strange

In the last chapter of Theology and Social Theory, Milbank begins his constructive theological project. In this book, he begins to expand on his Christology, pneumatology, and ecclesiology. There are some fantastic essays in this book. As I wrestle with this book more, I like it much more than on the first reading.

John Milbank and Catherine Pickstock, Truth in Aquinas

I must confess that I have only skimmed this book. My mentor and friend who is a church history professor at Trevecca believes that they read Aquinas correctly and dangerously so. This is by far probably the most controversial of the RO series since Thomists of all stripes have attacked it. I noticed this topic coming up quite frequently on your blog, and so I bumped it up the list. This is definitely an RO reading of Thomas. I would be interested in your thoughts.

Dan Bell, Liberation Theology after the End of History

This book is an excellent analysis of the Catholic liberation theology movement in Latin America. Bell sees that liberation theology lacked an ecclesiology capable of resisting capitalism. He provides an excellent analysis of capitalism, as well, focusing on how capitalism disciplines our desire making us into docile subjects. This is an outstanding work.

Conor Cunningham, Genealogy of Nihilism

Like Eric, I find this book to be profound. I am still working my way through it, but I see Cunningham addressing some of the frequent criticisms made of Milbank's work. I find his reading of nihilism to be fascinating.

Michael Hanby, Augustine and Modernity

I am shocked that this book does not get more attention. I read this book deeply as I read it in a directed reading I was taking on Augustine, and again in a class I took on Radical Orthodoxy. He takes apart the traditional modern claim that Augustine stands in direct line between Plato and Descartes in terms of the creation of the autonomous self. He also works through Augustine's Trinitarian theology and soteriology. Hanby articulates the idea of a doxological selfhood. This is a RO reading of Augustine.

Related to RO

William Cavanaugh, Torture and Eucharist

This is not in the RO series, but Cavanaugh has written an exceptional essay mentioned above. This book, though, provides an ecclesial example of how the core elements of RO look on the ground in resistance to the Pinochet regime. Words cannot express how excellent I find this book to be.

Stephen Long, The Goodness of God

Eric recommended Long's Divine Economy, which is published in the RO series. That is also an excellent book. However, this is my absolute favorite book of Long's (though I haven't read his most recent which I hear is also quite good).

Bell, Long and Cavanaugh are students of Hauerwas, to whom I am deeply indebted to for forming me as a Christian and a pastor. I confess that I am more Hauerwasian than RO, and that bias is probably represented in this list.

Critiques of RO

David Toole, Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo

I checked this book out on interlibrary loan, so I only had it for two weeks. It attempts to critique RO from the perspective of John Howard Yoder. Toole claims that ultimately Milbank is unable to outnarrate nihilism, because he lack an apocalyptic understanding of the world. I wish I had more time with this book because I think he raises some serious issues that RO has yet to address with regards to pacifism.

I hope this helps. There are several other books in the series as well as other related books that are coming out. I believe this is a good start.

Grace and Peace,

Scott

suggested reading

I'm relatively new to R.O. therefore I'm asking for suggestions on a reading list. I see that James K.A. Smith has developed a good bibliography, which needs to be updated. If you had to choose the first 3-10 books to read in regards to R.O., which ones would they be? Which books are the most important? The books that you suggest can either be from the R.O. Series or other books by the scholars of this camp. Thanks ahead of time for doing this for me.

Thursday, October 27, 2005

A Testimony to Ecumenism

On the Feast Day of William Temple

Today’s lectionary reading in the daily cycle brings us this passage from the Gospel of Matthew:

Matthew 13:18-23 (NRSV)

18 "Hear then the parable of the sower. 19 When anyone hears the word of the kingdom and does not understand it, the evil one comes and snatches away what is sown in the heart; this is what was sown on the path. 20 As for what was sown on rocky ground, this is the one who hears the word and immediately receives it with joy; 21 yet such a person has no root, but endures only for a while, and when trouble or persecution arises on account of the word, that person immediately falls away. 22 As for what was sown among thorns, this is the one who hears the word, but the cares of the world and the lure of wealth choke the word, and it yields nothing. 23 But as for what was sown on good soil, this is the one who hears the word and understands it, who indeed bears fruit and yields, in one case a hundredfold, in another sixty, and in another thirty."

One of the great oddities of contemporary American Christianity is its insistence on division as a means of holiness. It lacks either the creativity or comprehension of a faith that is vibrant enough to engage the world that surrounds it as an exile in the model of Jeremiah and diaspora Judaism. As a result, it attempts to manipulate the state into a means of spreading Christian dogma through legal means, consider it an Evangelical version of Franco’s Spain. Domination of the other seems to be one of its primary goals and it considers this goal as a means of converting the unbelievers.

Unlike this approach, Jesus offers us the parable of the sower and the seed. The seed is sown, God waters it, and it will grow depending on where it lands. This landing should probably not be understood in predestination terms (a la Calvin), rather it should be understood as the place we are when we hear it. The point is that the seed cannot be coerced into growing. The models of the Inquisition and of Franco are contrary to the gospel Jesus gives us.

Rather, in light of the testimony of William Temple, let us examine the beauty of the Elizabethan compromise. While this claim was certainly a political move, it also codified the via media. The idea that “all may, some should, none must" is at the heart of the Anglican via media. It presupposes the dignity of the human person and grants the freedom to make decisions free of coercion. It understands that the seed cannot be forced to grow; rather, the seed is best left sown and allowed to grow as it may. If it snatched away, it must be resown. If it is shallow, it will soon wither. If it is entangled in the cares of the world or the lure of wealth, it will not thrive. If it lands in good soil, it will blossom.

William Temple was renowned for his ecumenism. Ecumenism requires that Christians of varied traditions allow others to interpret specific passages and dogmas differently, yet understands that the resurrection of our Lord is at the center of Christian identity. It understands that we are the Body of Christ and dependant upon each other in order to truly reflect our Lord to the watching world. To use Milbank as an interlocutor, it understands that an ontology of peace allows for difference that creates harmony rather than chaos. We do not need homogeneity, we need to be the Body of Christ without schism or division in order to reflect the unity of our God. Holiness is certainly part of who God is, but separation need not be monastic or exclusionary. As Jesus sat with those that the holy called sinners, he reflected the Kingdom come.

On the feast day of William Temple, one of the doctors of the Anglican Church, let us celebrate the Church catholic. Let us hope for a day when we see more similarity with our brothers and sisters in the faith rather than our differences. As we work together for that day, let us be encouraged by the life and thought of William Temple and allow the seed to bear fruit a hundredfold.

Today’s lectionary reading in the daily cycle brings us this passage from the Gospel of Matthew:

Matthew 13:18-23 (NRSV)

18 "Hear then the parable of the sower. 19 When anyone hears the word of the kingdom and does not understand it, the evil one comes and snatches away what is sown in the heart; this is what was sown on the path. 20 As for what was sown on rocky ground, this is the one who hears the word and immediately receives it with joy; 21 yet such a person has no root, but endures only for a while, and when trouble or persecution arises on account of the word, that person immediately falls away. 22 As for what was sown among thorns, this is the one who hears the word, but the cares of the world and the lure of wealth choke the word, and it yields nothing. 23 But as for what was sown on good soil, this is the one who hears the word and understands it, who indeed bears fruit and yields, in one case a hundredfold, in another sixty, and in another thirty."

One of the great oddities of contemporary American Christianity is its insistence on division as a means of holiness. It lacks either the creativity or comprehension of a faith that is vibrant enough to engage the world that surrounds it as an exile in the model of Jeremiah and diaspora Judaism. As a result, it attempts to manipulate the state into a means of spreading Christian dogma through legal means, consider it an Evangelical version of Franco’s Spain. Domination of the other seems to be one of its primary goals and it considers this goal as a means of converting the unbelievers.

Unlike this approach, Jesus offers us the parable of the sower and the seed. The seed is sown, God waters it, and it will grow depending on where it lands. This landing should probably not be understood in predestination terms (a la Calvin), rather it should be understood as the place we are when we hear it. The point is that the seed cannot be coerced into growing. The models of the Inquisition and of Franco are contrary to the gospel Jesus gives us.

Rather, in light of the testimony of William Temple, let us examine the beauty of the Elizabethan compromise. While this claim was certainly a political move, it also codified the via media. The idea that “all may, some should, none must" is at the heart of the Anglican via media. It presupposes the dignity of the human person and grants the freedom to make decisions free of coercion. It understands that the seed cannot be forced to grow; rather, the seed is best left sown and allowed to grow as it may. If it snatched away, it must be resown. If it is shallow, it will soon wither. If it is entangled in the cares of the world or the lure of wealth, it will not thrive. If it lands in good soil, it will blossom.

William Temple was renowned for his ecumenism. Ecumenism requires that Christians of varied traditions allow others to interpret specific passages and dogmas differently, yet understands that the resurrection of our Lord is at the center of Christian identity. It understands that we are the Body of Christ and dependant upon each other in order to truly reflect our Lord to the watching world. To use Milbank as an interlocutor, it understands that an ontology of peace allows for difference that creates harmony rather than chaos. We do not need homogeneity, we need to be the Body of Christ without schism or division in order to reflect the unity of our God. Holiness is certainly part of who God is, but separation need not be monastic or exclusionary. As Jesus sat with those that the holy called sinners, he reflected the Kingdom come.

On the feast day of William Temple, one of the doctors of the Anglican Church, let us celebrate the Church catholic. Let us hope for a day when we see more similarity with our brothers and sisters in the faith rather than our differences. As we work together for that day, let us be encouraged by the life and thought of William Temple and allow the seed to bear fruit a hundredfold.

Tuesday, October 25, 2005

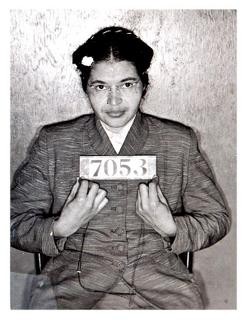

Enough Is Enough: A Devotion in Honor of Rosa Parks

Enough is Enough:

A Devotion in Honor of Rosa Parks

Acts 16:16-40

16As we were going to the place of prayer, we were met by a slave girl who had a spirit of divination and brought her owners much gain by fortune-telling. 17She followed Paul and us, crying out, "These men are servants of the Most High God, who proclaim to you the way of salvation." 18And this she kept doing for many days. Paul, having become greatly annoyed, turned and said to the spirit, "I command you in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her." And it came out that very hour.

A Devotion in Honor of Rosa Parks

Acts 16:16-40

16As we were going to the place of prayer, we were met by a slave girl who had a spirit of divination and brought her owners much gain by fortune-telling. 17She followed Paul and us, crying out, "These men are servants of the Most High God, who proclaim to you the way of salvation." 18And this she kept doing for many days. Paul, having become greatly annoyed, turned and said to the spirit, "I command you in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her." And it came out that very hour.

In the telling of the stories of the saints, we most often seek to narrate their lives through the stories given to us in the Holy Scriptures. This devotion is no exception. As I reflect on the life of Rosa Parks, immediately this narrative of Paul in Philippi came to mind. Paul is called to "help" in Macedonia, a place devoted to the cause of the Empire and the worship of Caesar. In other words, Macedonia was enemy territory, a land enslaved by the prinicipalities and powers. Of course, as the Book of Acts reveals time and again, slavery and imprisonment are not defined by chains and bars. Paul and Silas are followed daily by a slave girl who made her owners a great profit through fortune telling. Every day, she follows Paul and Silas and announces their identity to the crowds. One particular day, Paul decides that enough is enough and speaks, "I command you in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her." And the demon came out that very hour.

So who is Rosa Parks in this story? On one hand, it would be easy to compare her to the servant girl, forced by sheer power to serve unjust people to make them a profit. Certainly, the Jim Crow South established both legal and social structures to force African Americans to live in conditions little different than while slavery existed. Certainly, Mrs. Parks was set free by Christ to live free of the principalities and powers in a bold way. However, that is not the comparison I want to make this morning.

For me, Rosa Parks much more closely resembles the Apostle Paul. She was a woman of deep faith, and also a woman who worked hard. One day, on the bus ride home after a long day at work, a white man approached her and demanded that she give up her seat. That was the law after all. When asked, black people were expected to move to the back of the bus, without comment and without complaint. To do so would warrant arrest or far worse. On this particular day, Rosa Parks was probably not only tired but also irritated. She looked at the man, in the eye, and said, "No." She refused to give up her seat! Her act of public defiance of segregation was the first salvo in a battle to liberate the United States from the spirit of racism and exploitation that so thoroughly possess it. This shot heard round the world would not result in the instantaneous expulsion of the evil spirit, but it did begin the process of exorcism.

She was arrested, booked, and placed in jail. The principalities and powers probably imagined that the prospects of jail would frighten a woman into ending her defiance and do anything to escape imprisonment. However, bars do not a prison make. Far from being intimidated, Parks' arrest led her young pastor to stand up and join her in jail. Her announcement that enough is enough sounded a call to a generation of young students who were also both irritated and fearless. Within ten years, they would storm the bastions and redoubts most heavily devoted to the service of the spirit of racism. They conquered this spirit in a most unique way. You see, when Paul and Silas were locked in the deepest belly of the Philippian jail, chained and bound, they sang hymns and prayed to God. And then came a holy earthquake that shook the very moorings of the prison and of Roman society itself. I am sure that Rosa Parks and her young pastor prayed and sang because a great earthquake soon began to shake the moorings of a racist and exploitative social structure known as Jim Crow.

Casting out the evil spirits that possess not only individuals but also social structures is both an instantaneous and progressive movement. On that day in Philippi, the demon was cast out of the girl, and later that evening, the jailer was released from his imprisonment. It would take another three hundred years for Paul's command to be heard throughout the Roman Empire. On that day when Rosa Parks said no, the thralldom of the South to the spirit of racism began to wane; however, the collapse of principalities and powers takes time, is costly, and they do not go quietly into the night.

In remembering Rosa Parks, we must remember her call. Just as the Macedonian man spoke to Paul, asking for help, so too does the voice of Rosa Parks also speak to us some fifty years later. Enough is enough. The time has come for us to begin again to imagine the beloved community. The time has come for us to be willing to challenge the principalities and powers on their home turf, where they are most entrenched. It is time for the church to rise up together, sing our hymns, chant our Psalms, receive Christ's body and blood and be made into that body ourselves. For too long, when confronted by the evil spirits that have captured our age, we have stood and moved to the back of the bus. Rosa Parks was an ordinary woman, yet her actions emboldened a young pastor to step forward and be what his church demanded, a prophet leader who would stand firm and sound the call of justice and judgment, of peace and healing, of tearing apart and building up again.

Are we capable of hearing the wonderful testimony of Rosa Parks?

Monday, October 24, 2005

The Eucharist Makes the Church

The recent discussions on other blogs referrring to de Lubac and Ressourcement led me to call one of my dearest friends and mentors to ask him about this movement. He said that after he moved through Will Willimon, Hauerwas and the Duke school, he came to de Lubac and Ressourcement. He recommended the book, The Sacrament of Salvation: An Introduction to Eucharistic Ecclesiology, by Paul McPartlan. For those more familiar with Ressourcement, where does McPartlan fit in Catholic theology.

I am reading a two part interview with Father McPartlan conducted by Zenit. It is very interesting and quotes de Lubac that in the first millenium the Eucharist made the church, but in the second millenium switched to the church makes the Eucharist. I just wanted to post these two interviews and see what issues/thoughts come to mind.

Everything about Radical Orthodoxy pushes us towards the Eucharist as the center of our lives, and yet we all raise questions about the embodiment of just such a theology. I love the quote that begins the second interview:

Part 1 of the Interview Part 2 of the Interview

I am reading a two part interview with Father McPartlan conducted by Zenit. It is very interesting and quotes de Lubac that in the first millenium the Eucharist made the church, but in the second millenium switched to the church makes the Eucharist. I just wanted to post these two interviews and see what issues/thoughts come to mind.

Everything about Radical Orthodoxy pushes us towards the Eucharist as the center of our lives, and yet we all raise questions about the embodiment of just such a theology. I love the quote that begins the second interview:

"The Eucharist contains riches to feed and forgive us, to strengthen and unite us, and to guide and protect us on our pilgrim way."What are your thoughts?

Part 1 of the Interview Part 2 of the Interview

Sunday, October 23, 2005

Lectionary Readings for This Week

Joshua 3:7-17

Psalm 107:1-7, 33-37

1 Thessalonians 2:9-13

Matthew 23:1-12

Here are the readings for the week. What are your thoughts? What are your insights? What is at stake theologically in these readings?

Psalm 107:1-7, 33-37

1 Thessalonians 2:9-13

Matthew 23:1-12

Here are the readings for the week. What are your thoughts? What are your insights? What is at stake theologically in these readings?

Saturday, October 22, 2005

David Bentley Hart on Robert Jenson

First Things has an interesting article by David Bentley Hart, who wrote The Beauty of the Infinite, on the "neglected" theology of Robert Jenson. Hart discusses how Jenson may be the best American systematic theologian, and yet few American seminaries and religion programs address his Systematic Theology, vol. 1 and vol. 2. My understanding of the Trinity has been deeply shaped by Jenson's theology, and I always find his thought challenging, interesting, and truthful.

I'm just wondering, since we are a fairly diverse group, how much exposure do you have to Robert Jenson? What are your thoughts about his systematic theology?

Here is an outstanding article of his that was in First Things back in 1993.

Grace and Peace,

Scott

I'm just wondering, since we are a fairly diverse group, how much exposure do you have to Robert Jenson? What are your thoughts about his systematic theology?

Here is an outstanding article of his that was in First Things back in 1993.

Grace and Peace,

Scott

Friday, October 21, 2005

Dangerous Times Call for Drastic Measures

I still remember the first time I discovered that the world was a dangerous place.

Aunt Sally and Lib lived up on the hill in front of my house. Aunt Sally was a retired school teacher, and Lib was her mentally challenged younger sister. By the time I was born, they both seemed ancient. Their lives revolved around snooping (reading our mail), gossiping about family and neighbors, cleaning our little Methodist church, teaching Sunday School, and raising chickens. Their house was not one of my favorite destinations: I thought it smelled funny, and they liked my brother better, anyway. I did, however, really like the chickens. When new chicks were born, I spent many hours chasing them and getting flogged by the mother hen. Finally, one day at the age of 7, I achieved my life-long goal and actually found a chick that had been abandoned by her mother. I took this chick with me and nursed her, fed her, and carried her everywhere I went. For a few days, this chick was the center of my every waking moment. After school one day, my brother, who was 2, and I were in the yard playing with the chick. When my bird tried to run away, I yelled to my brother, "Stop it." He thought I yelled, "Stomp it." And the rest of course is history. I discovered on that day that the world was a violent and dangerous place.

After the funeral procession and burial, I waited the appropriate three days, and dug my chick up to see if she had come back from the dead (A boy can always hope). The chick was still dead, and eventually my mother made me stop digging her up. I then began to devise a system so that in the future, we could prevent such tragedies. I was determined to create a world where abandoned chicks would be safe. Since my mother would not let me take the instant option of giving my brother away, I developed rules (No brothers allowed around any future chicks), I fixed a box on my bookshelf that was beyond my brother's reach (I had to go to school), I worked on my brother's enunciation (stop and stomp mean different things), and tried to think through how I could make a dangerous world safe for chickens. Dangerous times call for drastic measures.

There is a powerful temptation for us to try to make the world safe. Over the past few weeks in Waycross, we have experienced the death of a teenager in a tragic car accident, a double murder at a convenience store committed by a 17 year old, and the conviction of a high school teacher to 35 years in prison for molesting a 15 year old student. Earthquakes in Pakistan, hurricanes in Louisiana, and roadside bombs in Iraq remind us just how dangerous the world is, and our inclination is to take any steps necessary to make the world safe for ourselves and for our children. Dangerous times call for drastic measures.

Israel discovered very early in her history just how dangerous the world is. From the beginning, she was surrounded by powerful neighbors, superpowers who constantly were at war with each other and with their neighbors. By the time Jesus was born, Israel felt daily the boot of Roman oppression: foreign occupation, high taxes, and the powerful temptation to abandon the Jewish faith for the faith of the Empire. All around them, the peoples of the world began to embrace the ways of the Romans: names, customs, even practices that were odious to Jews. Faithful Jewish parents feared what would happen to their children in such a dangerous world. The Pharisees were one of the groups that emerged in an effort to make the world safe for Jews.

They knew that their survival depended on keeping their identity. That in a world gone mad, they must remember who they were and who their God was. They established a way of life based on radical adherence to the Law, attempting to integrate the Law into every facet of their daily lives so that they could be a people who were completely faithful to God. They gave their lives to learning the 613 laws of the Torah and then working out how these laws should be carried out in their daily living. The Pharisees were far from evil; they were faithful people seeking to survive in a dangerous world.

Of course, when you live in a dangerous world, you have to make difficult decisions. When your survival depends on your morality, you cannot be weak-minded or overly tolerant. You must sacrifice the individual for the good of the whole community. Thus, sinners had to be excluded. The disabled had to be excluded. The weak had to be excluded. The system put in place to make the world safer had to be carried out with zeal, or all could be lost.

To say that Jesus threatened the security of the Pharisaical system is an understatement. When he rolled into town, he performed miracles that worked to restore the excluded back into the life of the community. He cast out demons; he healed the sick; he opened the eyes of the blind, and unstopped the ears of the deaf; he touched lepers and restored them to good health; he raised the dead. He ventured into the situations and places where they could not and would not go. Even more frightening, he taught with authority, and what he taught threatened to unravel the whole system. They erected a "wall" to protect the faithful from the evil of the unfaithful, and he threatened to disassemble the wall. He did this claiming to be speaking with the authority of God. He was dangerous. In a dangerous world, he threatened to destroy the very walls that protected them, their way of life, and the future lives of their children. In dangerous times, sometimes you have to take drastic measures.

Thus, when Jesus comes to Jerusalem and enters into the Temple, the Pharisees see this as their opportunity to test him and put him in his place. They are foiled with the Herodians in an attempt to trap Jesus with a question about Caesar. They retreat, and after Jesus silences the Sadducees, they return with a new question. They bring forward their best lawyer with their best question. "Teacher, which is the great commandment in the Law?" Whatever answer he gives will open him up to criticism. He will be put in his place.

Jesus' answer stuns them. He states that the greatest commandment is, of course, the first commandment: "You shall love the Lord with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind." He adds, "And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself." And there it is. Jesus quotes to them the bedrock of Jewish faith, to which no faithful Jew could ever disagree. Jesus places himself squarely in the middle of Jewish tradition. He even connects himself to an issue dear to the Pharisees, stating, "On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets." Jesus not only places himself within orthodox Jewish faith, his answers sound like answers a Pharisee would give! However, through his actions and teachings they know he has radicalized the idea of "neighbor." Jesus' conception of love and neighbor threaten to re-narrate the entire Jewish tradition as they stretch beyond the comfortable (and safe) walls erected by the Pharisees. To follow Jesus means to enter again into a dangerous world where people get hurt and everything might be lost. To follow Jesus is to realize that life is not in our immediate control. To follow Jesus would redefine what it means to love God with heart, soul, mind, and strength. In short, to follow Jesus would mean to tear down the walls and gates and risk everything to belief in God.

Jesus compounds their dilemma by asking them a question. "What do you think about the Christ? Whose son is he?" They answer, "The son of David." Jesus responds by quoting from Psalm 110, where David refers to the Messiah as "my Lord." Jesus asks, "If then David calls him Lord, how is he his son?" The Pharisees imagine the Messiah as one in the line of David who will rule them with strength and authority as David did, restoring their place in the world and defeating their enemies. Then, through the strength of his right arm, the world will be safe again. Jesus escalates the tension by proposing that the Messiah is more than a son of David, that he is also Lord of David, meaning, of course, that the Messiah is divine. While Jesus does not declare himself to be that Messiah, the move towards this conclusion is rapidly approaching for the Pharisees and for the entire Jewish religious hierarchy. He has thwarted each of their challenges and tests. He has now raised the stakes. The authority with which he teaches is not just being spoken on behalf of God. His authority stems from his speaking as God, as the Lord of David. At this point, Matthew tells us, "And no one was able to answer him a word, nor from that day did anyone dare to ask him anymore questions." The time for talk is over. The Pharisees withdraw to plan for what comes next. Dangerous times call for drastic measures. Jesus threatens the entire system, all of Jerusalem. Caiaphas will prophetically state, "It is better for one man to die than for the entire nation to perish" (John 11:49-50).

We also live in dangerous times. We live in the post-9/11 era, where as a society we have stopped asking questions. Being threatened, we simply withdraw to construct a safe place free from danger. We buy big cars that insulate us from the noise of driving through the poor sections and mobile home parks. We buy alarm systems to protect our homes. We move to the suburbs. We build more prisons, hire more police, get bigger guns. Yet crime goes up, and our feeling of safety becomes nothing more than an illusion. As a nation, we do not ask questions about what is going on. We are willing to do anything to give us the illusion of safety. In the name of safety, we are even willing to sacrifice our sons and daughters in foreign lands to give us the illusion that the world is safer. The reality is the world is a dangerous place, despite all of our efforts to make it "safer."

As the church, we also realize that the world is dangerous, and we realize that we also must take drastic measures. But what actions do we take? What do we do?

1) We can go with the Pharisees downwards on the path of the Law.

We can continue to try to build a safe world of our own making in our own image. It will appear safe on the surface, but will remain so only by herculean effort, smoke and mirrors, and mass deception. Ultimately, death and danger will stay away only as long as we continue to sacrifice our children to death. The cost of building walls, identifying enemies and destroying them is overwhelming. Safety comes at an ever-increasing cost and will ultimately fail. As St. Paul reveals, "The end of the Law is death."

2) We can go with Christ upwards on the path of Love.

We can confess that the world is dangerous, and that we will probably lose everything, including our lives. The path of love is risky and costly. Rather than building walls to keep out thosee we fear, the path of love journeys straight into the homes of our enemies, and it is a two way street. Instead of division, there is an invitation to fellowship. Instead of the sounds of unending war, there is the sound of people singing sweetly. Instead of a road littered with broken dreams and broken lives, there is a glorious parade headed up to the cross, where we can lay down our lives, not in the worship of the illusion of safety, but with the hope of resurrection and entrance into the kingdom of God.

During the early years of slavery in North America, slave masters often sought to convert their slaves to Christianity. However, as conversions grew rapidly amongst the slaves (more rapidly than in the white community), these conversions were ordered to end. In South Carolina slaves outnumbered plantation owners by a margin of over 9:1. Church services were frequently banned, unless they could be carefully controlled. We wouldn't want slaves reading about Moses, would we? Dangerous times call for drastic measures. There is one chilling story about a group of slaves who held worship services in a barn over a wash basin filled with water. In this context, they could sing, pray, and cry out to God without fear of being heard and beaten. One day, the overseeer discovered their worship service, and with a whip violently broke up the service. Everyone ran for cover except for one man, who continued to pray while the overseer whipped him. His prayer was "Father, forgive him for he knows not what he does!"

Dangerous times call for drastic measures. Instead of being a people known for wielding the whip without questions, can we be a people able to feel the bite of the lash and still forgive our enemies? Could our drastic measures be becoming a people who trust so much in the Lord that we are willing to believe that our salvation comes from worshiping God with all of our heart, soul, and mind? Would we be a people willing to love our neighbor as ourself even if our neighbor hates us?

On a dangerous morning in a dangerous land, will you take the drastic step of coming to His table? Know that this is a dangerous journey and a dangerous meal. It is a table where questions are asked and truthful answers are given. Prejudice and hatred are present, but they are being washed away in baptism. Sin is not ignored, but it is confessed. Death is not denied, but it is defeated. As you eat from this table, a miraculous transformation will take place, our bodies together will become His body. Our drastic measure is nothing more than to be His body broken for the world and His blood spilled for the salvation of the world. To eat this meal is an invitation out of the violence of the world and into the peace of God's kingdom. Will you come this morning?

Aunt Sally and Lib lived up on the hill in front of my house. Aunt Sally was a retired school teacher, and Lib was her mentally challenged younger sister. By the time I was born, they both seemed ancient. Their lives revolved around snooping (reading our mail), gossiping about family and neighbors, cleaning our little Methodist church, teaching Sunday School, and raising chickens. Their house was not one of my favorite destinations: I thought it smelled funny, and they liked my brother better, anyway. I did, however, really like the chickens. When new chicks were born, I spent many hours chasing them and getting flogged by the mother hen. Finally, one day at the age of 7, I achieved my life-long goal and actually found a chick that had been abandoned by her mother. I took this chick with me and nursed her, fed her, and carried her everywhere I went. For a few days, this chick was the center of my every waking moment. After school one day, my brother, who was 2, and I were in the yard playing with the chick. When my bird tried to run away, I yelled to my brother, "Stop it." He thought I yelled, "Stomp it." And the rest of course is history. I discovered on that day that the world was a violent and dangerous place.

After the funeral procession and burial, I waited the appropriate three days, and dug my chick up to see if she had come back from the dead (A boy can always hope). The chick was still dead, and eventually my mother made me stop digging her up. I then began to devise a system so that in the future, we could prevent such tragedies. I was determined to create a world where abandoned chicks would be safe. Since my mother would not let me take the instant option of giving my brother away, I developed rules (No brothers allowed around any future chicks), I fixed a box on my bookshelf that was beyond my brother's reach (I had to go to school), I worked on my brother's enunciation (stop and stomp mean different things), and tried to think through how I could make a dangerous world safe for chickens. Dangerous times call for drastic measures.

There is a powerful temptation for us to try to make the world safe. Over the past few weeks in Waycross, we have experienced the death of a teenager in a tragic car accident, a double murder at a convenience store committed by a 17 year old, and the conviction of a high school teacher to 35 years in prison for molesting a 15 year old student. Earthquakes in Pakistan, hurricanes in Louisiana, and roadside bombs in Iraq remind us just how dangerous the world is, and our inclination is to take any steps necessary to make the world safe for ourselves and for our children. Dangerous times call for drastic measures.

Israel discovered very early in her history just how dangerous the world is. From the beginning, she was surrounded by powerful neighbors, superpowers who constantly were at war with each other and with their neighbors. By the time Jesus was born, Israel felt daily the boot of Roman oppression: foreign occupation, high taxes, and the powerful temptation to abandon the Jewish faith for the faith of the Empire. All around them, the peoples of the world began to embrace the ways of the Romans: names, customs, even practices that were odious to Jews. Faithful Jewish parents feared what would happen to their children in such a dangerous world. The Pharisees were one of the groups that emerged in an effort to make the world safe for Jews.

They knew that their survival depended on keeping their identity. That in a world gone mad, they must remember who they were and who their God was. They established a way of life based on radical adherence to the Law, attempting to integrate the Law into every facet of their daily lives so that they could be a people who were completely faithful to God. They gave their lives to learning the 613 laws of the Torah and then working out how these laws should be carried out in their daily living. The Pharisees were far from evil; they were faithful people seeking to survive in a dangerous world.

Of course, when you live in a dangerous world, you have to make difficult decisions. When your survival depends on your morality, you cannot be weak-minded or overly tolerant. You must sacrifice the individual for the good of the whole community. Thus, sinners had to be excluded. The disabled had to be excluded. The weak had to be excluded. The system put in place to make the world safer had to be carried out with zeal, or all could be lost.

To say that Jesus threatened the security of the Pharisaical system is an understatement. When he rolled into town, he performed miracles that worked to restore the excluded back into the life of the community. He cast out demons; he healed the sick; he opened the eyes of the blind, and unstopped the ears of the deaf; he touched lepers and restored them to good health; he raised the dead. He ventured into the situations and places where they could not and would not go. Even more frightening, he taught with authority, and what he taught threatened to unravel the whole system. They erected a "wall" to protect the faithful from the evil of the unfaithful, and he threatened to disassemble the wall. He did this claiming to be speaking with the authority of God. He was dangerous. In a dangerous world, he threatened to destroy the very walls that protected them, their way of life, and the future lives of their children. In dangerous times, sometimes you have to take drastic measures.

Thus, when Jesus comes to Jerusalem and enters into the Temple, the Pharisees see this as their opportunity to test him and put him in his place. They are foiled with the Herodians in an attempt to trap Jesus with a question about Caesar. They retreat, and after Jesus silences the Sadducees, they return with a new question. They bring forward their best lawyer with their best question. "Teacher, which is the great commandment in the Law?" Whatever answer he gives will open him up to criticism. He will be put in his place.

Jesus' answer stuns them. He states that the greatest commandment is, of course, the first commandment: "You shall love the Lord with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind." He adds, "And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself." And there it is. Jesus quotes to them the bedrock of Jewish faith, to which no faithful Jew could ever disagree. Jesus places himself squarely in the middle of Jewish tradition. He even connects himself to an issue dear to the Pharisees, stating, "On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets." Jesus not only places himself within orthodox Jewish faith, his answers sound like answers a Pharisee would give! However, through his actions and teachings they know he has radicalized the idea of "neighbor." Jesus' conception of love and neighbor threaten to re-narrate the entire Jewish tradition as they stretch beyond the comfortable (and safe) walls erected by the Pharisees. To follow Jesus means to enter again into a dangerous world where people get hurt and everything might be lost. To follow Jesus is to realize that life is not in our immediate control. To follow Jesus would redefine what it means to love God with heart, soul, mind, and strength. In short, to follow Jesus would mean to tear down the walls and gates and risk everything to belief in God.

Jesus compounds their dilemma by asking them a question. "What do you think about the Christ? Whose son is he?" They answer, "The son of David." Jesus responds by quoting from Psalm 110, where David refers to the Messiah as "my Lord." Jesus asks, "If then David calls him Lord, how is he his son?" The Pharisees imagine the Messiah as one in the line of David who will rule them with strength and authority as David did, restoring their place in the world and defeating their enemies. Then, through the strength of his right arm, the world will be safe again. Jesus escalates the tension by proposing that the Messiah is more than a son of David, that he is also Lord of David, meaning, of course, that the Messiah is divine. While Jesus does not declare himself to be that Messiah, the move towards this conclusion is rapidly approaching for the Pharisees and for the entire Jewish religious hierarchy. He has thwarted each of their challenges and tests. He has now raised the stakes. The authority with which he teaches is not just being spoken on behalf of God. His authority stems from his speaking as God, as the Lord of David. At this point, Matthew tells us, "And no one was able to answer him a word, nor from that day did anyone dare to ask him anymore questions." The time for talk is over. The Pharisees withdraw to plan for what comes next. Dangerous times call for drastic measures. Jesus threatens the entire system, all of Jerusalem. Caiaphas will prophetically state, "It is better for one man to die than for the entire nation to perish" (John 11:49-50).

We also live in dangerous times. We live in the post-9/11 era, where as a society we have stopped asking questions. Being threatened, we simply withdraw to construct a safe place free from danger. We buy big cars that insulate us from the noise of driving through the poor sections and mobile home parks. We buy alarm systems to protect our homes. We move to the suburbs. We build more prisons, hire more police, get bigger guns. Yet crime goes up, and our feeling of safety becomes nothing more than an illusion. As a nation, we do not ask questions about what is going on. We are willing to do anything to give us the illusion of safety. In the name of safety, we are even willing to sacrifice our sons and daughters in foreign lands to give us the illusion that the world is safer. The reality is the world is a dangerous place, despite all of our efforts to make it "safer."

As the church, we also realize that the world is dangerous, and we realize that we also must take drastic measures. But what actions do we take? What do we do?

1) We can go with the Pharisees downwards on the path of the Law.

We can continue to try to build a safe world of our own making in our own image. It will appear safe on the surface, but will remain so only by herculean effort, smoke and mirrors, and mass deception. Ultimately, death and danger will stay away only as long as we continue to sacrifice our children to death. The cost of building walls, identifying enemies and destroying them is overwhelming. Safety comes at an ever-increasing cost and will ultimately fail. As St. Paul reveals, "The end of the Law is death."

2) We can go with Christ upwards on the path of Love.

We can confess that the world is dangerous, and that we will probably lose everything, including our lives. The path of love is risky and costly. Rather than building walls to keep out thosee we fear, the path of love journeys straight into the homes of our enemies, and it is a two way street. Instead of division, there is an invitation to fellowship. Instead of the sounds of unending war, there is the sound of people singing sweetly. Instead of a road littered with broken dreams and broken lives, there is a glorious parade headed up to the cross, where we can lay down our lives, not in the worship of the illusion of safety, but with the hope of resurrection and entrance into the kingdom of God.

During the early years of slavery in North America, slave masters often sought to convert their slaves to Christianity. However, as conversions grew rapidly amongst the slaves (more rapidly than in the white community), these conversions were ordered to end. In South Carolina slaves outnumbered plantation owners by a margin of over 9:1. Church services were frequently banned, unless they could be carefully controlled. We wouldn't want slaves reading about Moses, would we? Dangerous times call for drastic measures. There is one chilling story about a group of slaves who held worship services in a barn over a wash basin filled with water. In this context, they could sing, pray, and cry out to God without fear of being heard and beaten. One day, the overseeer discovered their worship service, and with a whip violently broke up the service. Everyone ran for cover except for one man, who continued to pray while the overseer whipped him. His prayer was "Father, forgive him for he knows not what he does!"

Dangerous times call for drastic measures. Instead of being a people known for wielding the whip without questions, can we be a people able to feel the bite of the lash and still forgive our enemies? Could our drastic measures be becoming a people who trust so much in the Lord that we are willing to believe that our salvation comes from worshiping God with all of our heart, soul, and mind? Would we be a people willing to love our neighbor as ourself even if our neighbor hates us?

On a dangerous morning in a dangerous land, will you take the drastic step of coming to His table? Know that this is a dangerous journey and a dangerous meal. It is a table where questions are asked and truthful answers are given. Prejudice and hatred are present, but they are being washed away in baptism. Sin is not ignored, but it is confessed. Death is not denied, but it is defeated. As you eat from this table, a miraculous transformation will take place, our bodies together will become His body. Our drastic measure is nothing more than to be His body broken for the world and His blood spilled for the salvation of the world. To eat this meal is an invitation out of the violence of the world and into the peace of God's kingdom. Will you come this morning?

Thursday, October 20, 2005

Wednesday, October 19, 2005

Beyond Morality: The Five Notes of the Gospel